Modern-day Melungeons who are rediscovering their Jewish ancestry are faced with asking:

- For how many generations was my family aware of their heritage?

- How was this information transmitted and by whom?

- Is it anywhere written down, preserved or recorded?

- Who else knew about us, and what did they know?

- When and how were decisions made to bury this information?

- Is it even possible for a family to have held onto vestiges of this heritage and passed them down for 500 years?

The answer to that last question is yes. For her book Suddenly Jewish: Jews Raised as Gentiles Discover Their Jewish Roots, Barbara Kessel interviewed descendants of Spanish settlers of the American Southwest.

Many of the original Europeans in the Southwest were Crypto-Jews who lived outwardly as Catholics but secretly as Jews, and their descendants are just now learning about their true heritage. Many are converting to Judaism. Kessel quoted one interviewee as saying, “…five hundred years and now I find myself home…You can be away five hundred years and then come home… Nobody said Kaddish (the Jewish Mourners’ Prayer) for this family for five hundred years. This will be my project.”

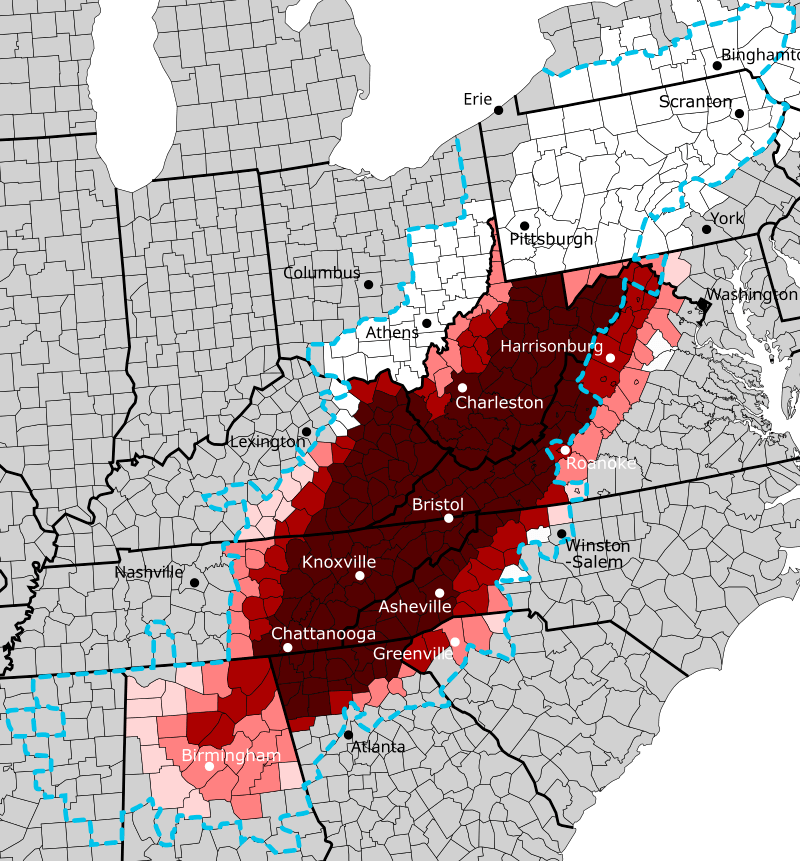

If families in the Southwest can hold onto and pass down, even in small ways, information about their heritage, it certainly can also be true of Melungeon families in Appalachia.

Also from Kessel’s book, “Parents who deny their Jewishness inevitably send out signals. They leave clues that their children pick up on, though neither side – parent or child- may be consciously aware of what is happening.”

Kessel quotes Canadian psychiatrist Robert Krell, “I think it’s hard for parents not to, from time to time, give a hint. There may be a thousand slips of the tongue which the child does not connect to being Jewish. Yet there is a subtle awareness. The question becomes: when does the observation get crystallized by the child into the construct,’Perhaps I am a Jew?’”

My Family’s Journey

I often wonder when in my family the decision was made to hide our Jewish heritage. I now know that I am Melungeon and Sephardic (Jewish from the Iberian peninsula, that is, Spain and Portugal) on both sides of my family and also Askenazic (Jewish from Eastern Europe) on my father’s side.

Both my mother and my father knew they were Jewish but hid that fact and lived as Christians. My grandparents were nominal Christians, as were some of my great grandparents. Whatever led my family to decide to hide their heritage, that decision was certainly cemented in the early 1900s.

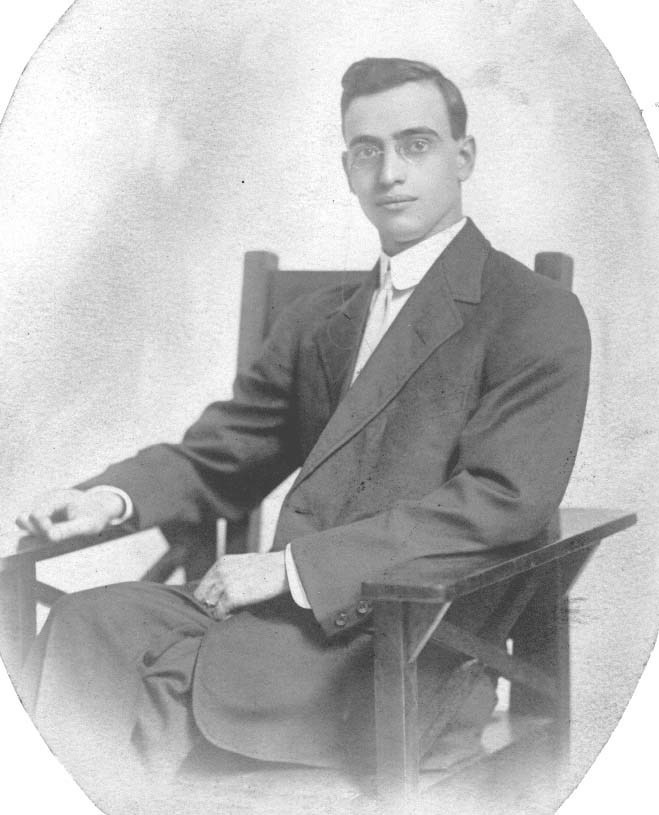

One of my great grandfathers, an attorney and newspaper editor and publisher, was serving in the Georgia State Legislature in 1913-1914 during the time of the arrest and trial of Jewish businessman Leo Frank. My great grandfather was described in Atlanta newspaper reports as being “broad and liberal in his views,” and he was noted for voting for progressive legislation. He would have been well-known by other newspaper editors and prominent politicians of his day.

My great grandfather, Travis Glenn Dorough

Leo Frank, who was the Jewish superintendent of a factory in Atlanta, was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death in August, 1913. In 1915, the governor of Georgia commuted Frank’s sentence to life in prison. By that time anti-Semitism was rampant in Georgia, a former governor was calling for the people to form mobs, and my great grandfather was no longer serving in state government. On August 17, 1915, a lynch mob literally attacked the state prison where Frank was being held, transported him 150 miles, and hanged him.

(Evidence later uncovered, although not conclusive, pointed to another man as the murderer, and in 1986, Frank finally was granted a posthumous pardon.)

Leo Frank (Photo credit: https://thebreman.org/research/leo-frank/)

In the aftermath of the lynching, lawyer, newspaper editor and politician Tom Watson called for a revival of the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia and throughout the South. The Klan sought a charter from the Georgia Secretary of State and was officially revived in November of 1915.

By 1920, Tom Watson was serving in the U.S. Senate and declaring himself to be “King of the Ku Klux.” Klan chapters were being organized throughout the South, and Klan marches were being held in major cities. Watson, now an open racist and member of the Klan, had once been seen as the progressive leader of the Populist Party in Georgia, the party of which my great grandfather had been a member.

Tom Watson (Photo credit: https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/thomas-e-watson-1856-1922/)

I don’t know if my great grandfather was Jewish, but my great grandmother had Melungeon and Jewish ancestry, and it was in 1920, in the midst of KKK threats and marches that my great grandparents loaded up their 6 daughters in a wagon and fled in the night to another county in North Georgia where they felt they would be safer. One of those daughters, Annie, was Black and had been taken into the family as a child. My grandmother told me that Annie was raised as their sister.

My father’s family was in North Carolina and would have faced similar threats. My father’s grandmother always insisted they were “Black Dutch,” and warned my father against ever researching his ancestry.

Thus, families that had not already hidden their Jewish ancestry certainly began to hide it in the 1920s.